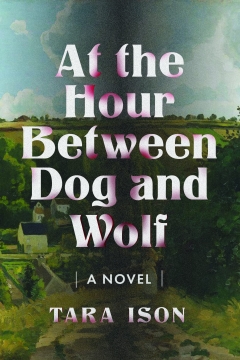

New novel underscores timeliness of historical lessons from the Holocaust

Never again.

A simple phrase; two small words to represent the magnitude of a global commitment to forever stand against the atrocities of the Holocaust.

Yet, as International Holocaust Remembrance Day is recognized on Jan. 27 this year, societies across the world continue to see an alarming affinity among certain groups with ideologies that would seem to threaten that solemn promise.

As many find themselves wondering how after nearly a century of apparent progress that can possibly still be the case, Arizona State University Professor Tara Ison’s latest novel, “At the Hour Between Dog and Wolf,” may provide some answers.

In it, the young protagonist who begins as a carefree Jewish girl goes into hiding during the German occupation of France, where she must assume the identity of a Catholic orphan to survive. By the end of the novel, she has transformed into an anti-Semitic, fervent disciple of fascism.

Although Ison didn’t set out to write a political book (it has been more than 25 years in the making), she readily acknowledges the timeliness of its themes.

The author of three revered fiction novels and a collection of short stories, Ison knows the importance of research and getting the facts right when it comes to writing an impactful narrative based in historical reality. This spring, she is sharing that knowledge with ASU students in a research-based fiction course.

On March 2, the general public will have a chance to glean from Ison’s wealth of experience when she is scheduled to give a reading from “At the Hour Between Dog and Wolf,” followed by a conversation with fellow ASU Professor Devoney Looser at Changing Hands Bookstore in Phoenix.

ASU News readers can enjoy a preview of what’s to come in the Q&A below.

Editor's note: Answers have been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Question: How did your latest novel, “At the Hour Between Dog and Wolf” — I love that title, by the way — how did it come about?

Answer: I will tell you a quick story about the title. For many, many years, I've referred to the project in my head as “The Hidden Child Novel,” but I didn't want that as the final title. Then, as part of my research — I don't even know how I came upon it — but there's a French idiomatic expression, “the hour between dog and wolf,” and it means twilight, or dusk. It’s something someone might say literally about the time of day, but the novel is so much about psychological transformation that it felt really meaningful to me on a figurative or a psychological level.

I have been working on this book for over 25 years. After my Alcatraz novel was published, I was thinking about my next book. And my stepmother — who I've known since I was 12 years old, and I'm very close to — she was a hidden child in World War II, in Hungary, a little Jewish girl. She was 5 years old. She doesn't remember a lot of the experience, but she remembers being given a false name. She remembers being taught the Catholic prayers, and she remembers being told if the police ever come, run away. And don't ever cry. Don't ever cry. It's a hard thing to expect from a 5-year-old.

And the idea of that experience absolutely fascinated me. But this story is not my stepmother’s story. I decided to make my character older; she's 12 when it all starts. And I decided to set the book in France, because I knew a little bit more about French culture. And the whole point of this story is that she begins as a very sort of secular Jewish, sophisticated little girl. And by the end of the novel, because the stakes are so high that she has to fake this new identity as a little Catholic orphan, she gets sort of brainwashed, and she transforms into a devout Catholic and also an anti-Semitic fascist. So I was just really interested in how that psychological trajectory could happen. How fragile identity is and how the pernicious power of right-wing extremist fascist ideologies can warp a human mind.

Q: It’s definitely fascinating, and also very timely. One review of the novel that struck me said how it “considers that moment between dusk and night, the almost imperceptible shift into darkness, both political and personal, as it exposes the high cost of accommodation of evil and bigotry.”

A: I never set out to write a political book. I was interested in the psychology of the character. And then, you know, about six or seven years ago, while I was still working on the book, I was horrified to realize that some of the passages in the book, some of the things that the characters are thinking and feeling, are happening right now, are being said right now, are being acted upon right now. So yes, from that perspective, it is a very unfortunately timely book.

Q: You've written a collection of essays, but your short stories are fiction, all of your novels are fiction, and you teach fiction as well. What about the fiction genre appeals to you as a means of expression, as opposed to something like memoir or poetry?

A: Someone once said write the book you want to read. And I think that, for both the novels and the short stories I've written, because I love reading so much, if the idea for a story, or a character, or an incident, or a setting — whatever it is — comes to me and I’ve never read that particular story, it gets under my skin. And I get this feeling of, well, I'm going to have to write it. I think another aspect of it is escape. Very similar to why people read novels and short stories, I think, is the desire to escape into another world by creating it. Any story you tell, you are bringing a new world into being, and you are bringing new people into creation. And that's very powerful. But it's also a responsibility, especially if you are writing a story that has any connection at all to a real person, a real incident, a real time in history. You have a responsibility to honor that real experience. Partly to create a sense of authenticity and verisimilitude, but also out of respect to the people whose world I’m trying to enter into as a stranger and capture on the page.

Q: You did an extensive amount of research for this latest novel, and you're teaching a course this spring on research-based fiction. Tell me a little bit about your research process and what parts of that you use to inform your teaching.

A: I love doing research. I prefer doing research over writing. Because I can be reading other books or old magazines or newspapers, or watching a documentary or a miniseries or movie, and I can still tell myself I'm working on the book (laughs). But for me, the process of research and the process of writing the book are very symbiotic; they coexist. It's not like I do all my research, and then I sit down and write. I do a certain amount of research at first to familiarize myself with the broad strokes of the world or the topic, or whatever it is, just to help me start shaping the story. But then I continue to research as I write. And there’s this thrill of discovering tiny little moments of history that can directly affect my characters’ lives and the choices that they make, that is amazing. So I might have a broad idea of the story, of the narrative, but I find myself constantly reshaping it in order to either accommodate the research or to utilize the research in a way that I hadn't expected.

So that, to me, is research on a very literal level. But I always want research to function on multiple levels. When I wrote my first novel, “(A Child out of) Alcatraz,” I had done four years of research on that, and I had incorporated every single fact and figure I had learned. And my editor came back to me and said, “You have got to cut at least half of this information.” So I went back and I thought, “OK, here's my rule.” Actually, I have two rules. One: How does this research personally connect to my character's experience? How does it touch them in some way? And two: Is there some kind of thematic, metaphorical, figurative jewel I can hone in this? And I got rid of everything else. Because I realized that by including everything, I was just showing off all my research (laughs). And it was dragging down the story, and I wasn't writing a nonfiction history book, and it wasn't relevant and etc., etc.

So for me — and this affects my teaching also, because I love teaching research-based fiction — one of the goals is learning to be selective about detail. You might read an entire 350-page nonfiction book about your subject, and you might wind up with only a couple of sentences that directly relate to or affect your character. But all of that other reading was not for nothing. It still informs your understanding of this world, even if you aren't explicitly including a certain fact or a certain figure; it still is immersing you in this other world. In a way, that is going to create authenticity and verisimilitude. So one of the challenges is the selection of detail.

The other sort of principle I talk about a lot when teaching research-based fiction is, it isn't interesting if it's just information; it has to be experienced. If you're just writing information about what happened when the Nazis invaded Paris, you know, that's a chapter in a history book. Fiction is about the character's experience of the Nazi occupation of Paris. That is what's interesting. There's a great quotation from E. L. Doctorow that I begin the (research-based fiction) course with. He says, “The historian will tell you what happened. The fiction writer will tell you how it felt.” And that is just the whole theory behind research-based fiction beautifully crystallized to me.

Top photo of ASU English Professor Tara Ison by Charlie Leight/ASU News