Study of California groundwater prompts a wake-up call for Arizona

A team of scientists that pioneered methods to observe changes in global groundwater stores over the past two decades using a specialized NASA satellite mission has made a surprising discovery about the aquifers that supply California’s Central Valley region.

Despite the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act adopted in 2014 to prevent overpumping and stabilize the aquifers, the groundwater depletion rate has accelerated to a point where groundwater could disappear over the next several decades. The act gives the state’s local groundwater management districts until 2042 to reach sustainability goals.

Renowned water scientist Jay Famiglietti is the lead researcher of a scientific team that published a paper in Nature Communications in December 2022 that details their analysis.

Famiglietti has a blunt message: “All around the world, we have been kicking the can down the road for a long time on effectively managing groundwater. Now we are at the end of the road, and it’s a dead end." Famiglietti is a professor with the Arizona State University School of Sustainability in the College of Global Futures, a unit of the Julie Ann Wrigley Global Futures Laboratory.

Famiglietti joined ASU in January to assist in developing the new Arizona Water Innovation Initiative, established through a $40 million investment by the state of Arizona.

Among the world’s most productive agricultural areas, California’s Central Valley grows most of the produce consumed across North America. To do that, it relies heavily on aquifers — as much as 100% during droughts. While groundwater has been disappearing from the region for almost a century, the increasing rate of drawdown in recent years is completely unsustainable, Famiglietti said.

“If that water disappears, so does food production. That means less produce, higher prices, shortages and other shocks to food systems,” said Famiglietti, previously the Canada 150 Research Chair in Hydrology and Remote Sensing at the University of Saskatchewan and executive director of USask’s Global Institute for Water Security.

“My fear is that if we wait 20 years to bring these aquifers to sustainability, there may not be anything left,” he said. “Speeding up the implementation period may be worth considering, because there appears to be a rush to pump as much as possible before the hammer comes down.”

ASU Professor Jay Famiglietti

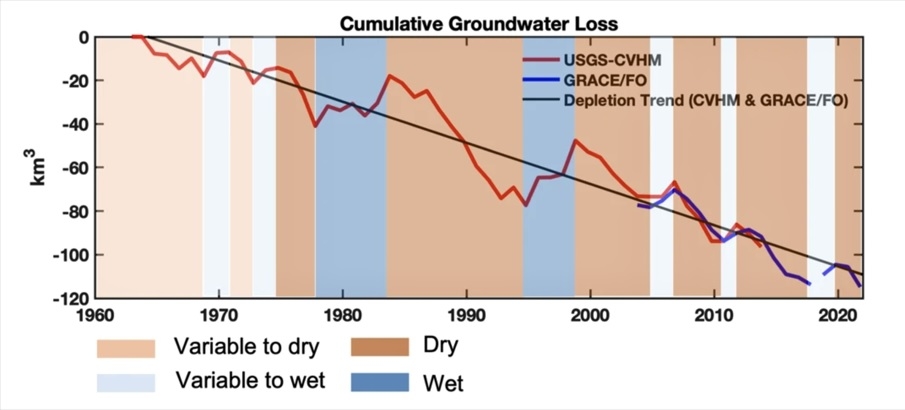

His team analyzed nearly two decades of data collected by NASA’s Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment satellite and the GRACE Follow-On satellite. Their research shows groundwater losses during 2019 to 2021 — the driest three-year period in California’s history — were 31% faster than in two previous drought periods of 2006 to 2011 and 2011 to 2017. This rate is also nearly five times greater than the long-term average rate of depletion since 1962.

Deep groundwater took millions of years to accumulate, Famiglietti said, and the current scale and pace of the depletion means that recharging the supply is virtually impossible.

“We talk about managed aquifer recharge and replenishing some of these aquifers. But that’s a small amount of water, and it’s close to the surface. This is industrial scale mining of groundwater, with virtually no chance on human time scales to replace the losses.”

The impacts of depletion extend far beyond food production, he said. A big issue is the subsidence, or sinking of the ground, which can potentially affect about one-quarter of the Central Valley.

Water for desert cities, including in major U.S. cities such as Phoenix, Las Vegas, Tucson, Arizona, and Salt Lake City, will be also scarcer, he said.

As groundwater disappears, there is ecological damage as wetlands are drained and streams run dry. And as water tables fall, costs increase to dig deeper wells and pump groundwater higher, creating affordability problems for people who need to access the water. Additionally, the poorer quality of deep water makes its treatment expensive.

Groundwater losses combining the USGS’s Central Valley Hydrologic Model and the GRACE/FO estimates since 1962. The black line represents the overall groundwater depletion from 1962 to 2021, calculated by combining the CVHM and GRACE estimates.

What’s happening in the Central Valley is also happening in the Lower Colorado Basin, the southern part of the High Plains Ogallala Aquifer, the Middle East, India and Bangladesh, and several other major food-producing regions around the world, he said.

This depletion of groundwater should be a wake-up call for Arizona, where groundwater constitutes 40% of the state’s water supply and contributes 43% to its GDP. Yet, outside of the state’s 5 Active Management Areas, groundwater is largely unregulated.

“Arizona is at a crossroads with its groundwater use,” said Famiglietti. “The management decisions it makes today, including how to allocate groundwater for cities, agriculture, industry and the environment, will largely determine its vitality over the next century.

“An important first step will be to carefully measure how much groundwater we actually have in Arizona and how much we are using, so that we can balance that with declining surface water availability from the Colorado River. We need to be able to support innovation and food production, but we need to do it for centuries, not just for a few decades.”

Sarath Peiris with the University of Sasketchewan contributed to this article.