What can human remains tell us about climate change? A lot, according to a new research article

Learning how people across the world coped with rapid climate change (RCC) throughout history can help current populations prepare, said a group of scientists.

Their paper on the subject, “Climate change, human health, and resilience in the Holocene,” was published in the January issue of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS). The article outlines what worked — and what didn’t work — historically for humans during climate change.

Using case studies, the scientists examined human remains and relationships between people during times of RCC. The article discusses how climate change had an impact on health, food stability, disease, migration and dispelled myths of violence during hard times.

“The human remains themselves are vital for explorations of the impact of climate and environmental change on individuals and groups in the past,” said Jane Buikstra, co-author and Regents Professor at the School of Human Evolution and Social Change at Arizona State University. “The archaeological record provides a window into both short- and long-term changes in human groups as a result of different forms of climate change.”

Professor Gwen Robbins Schug, with the University of North Carolina at Greensboro, was lead author of the paper. Co-authors included an international group of bioarchaeologists and archaeologists, including four professors from the School of Human Evolution and Social Change who are members of the Center for Bioarchaeological Research.

“We as bioarchaeologists have time depth that we can access by looking at human remains from past populations who’ve gone through things like climate change, who’ve experienced immigration or outmigration,” said Brenda Baker, associate professor of bioarchaeology at the School of Human Evolution and Social Change and co-author of the article. “And we have a handle on how people coped with that in the past, and that can help inform decisions we make today.”

So, what worked the best? Flexibility.

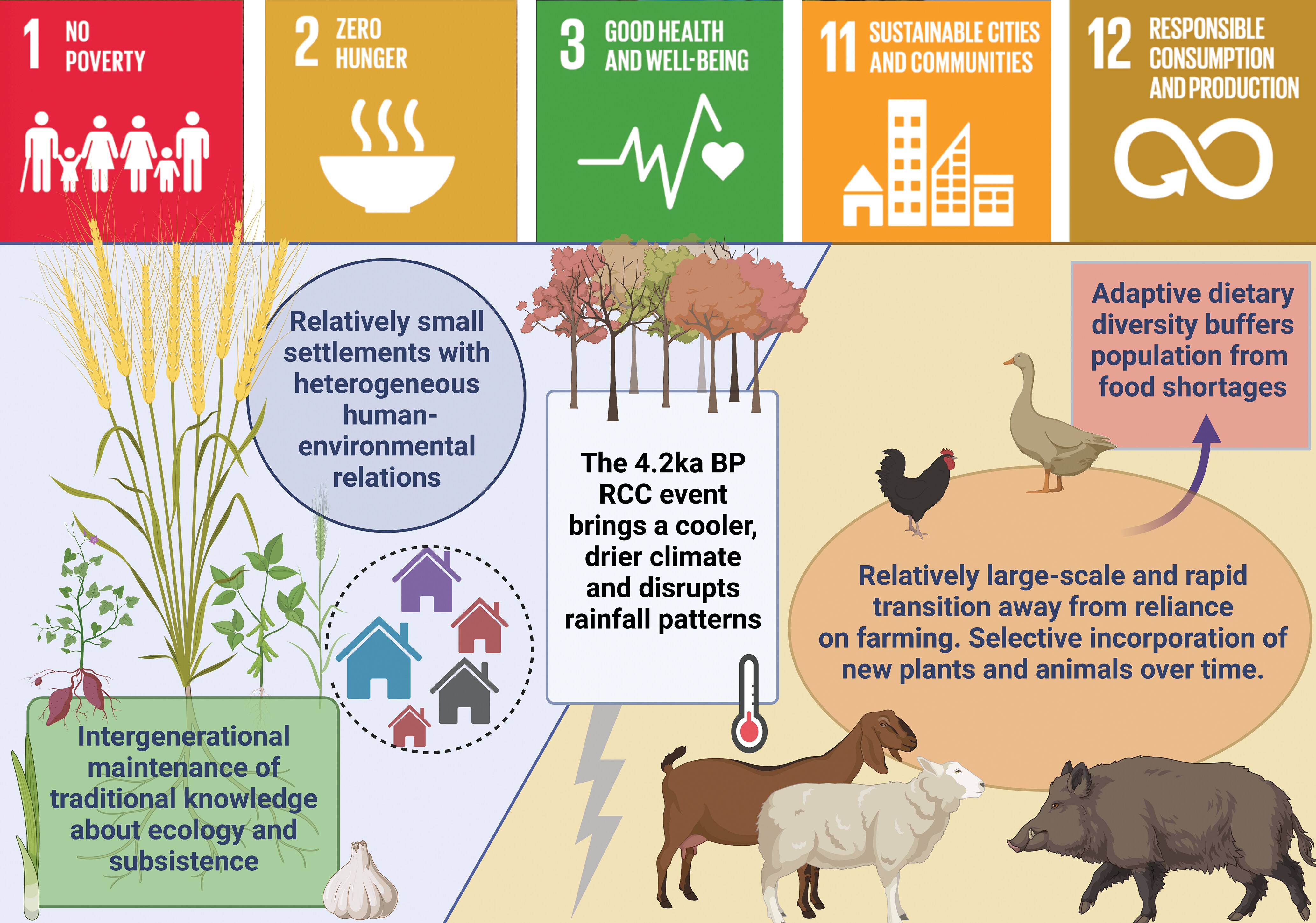

Diverse pathways to resilience relevant to the U.N. Sustainable Development Goals. Graphic courtesy PNAS

“Our research demonstrates the consequences of climate change events in human history have been most destructive for hierarchical, urban societies that lack flexibility to respond to environmental challenges,” the authors said in a press release. “Small-scale communities fare best when they maintain traditional knowledge of local ecology and diverse subsistence practices, are able to be mobile when circumstances require it, and when they sustain mutually beneficial relationships with neighboring communities.”

Examples of flexibility included incorporating new plants and animals as the climate changed, moving from a very large group of people into smaller societies to live and having a power distribution so not one person, or group of people, had control.

Another important result from the study are the misconceptions throughout history that climate change directly caused violence among people. The researchers explained that violence is not always a consequence — it mainly happened in large, hierarchical urbanized societies where socioeconomic inequality existed.

Along with an increased risk of violence, larger, less flexible urbanized societies were also at an increased risk for disease. One case study example used is that of the Black Death in England. The scientists explained that mental stress and overcrowding may have weakened people physically before the plague arrived.

“Bioarchaeology confirms that environmental migration, competition, interpersonal violence and societal collapse are not inevitable in the face of rapid climate change,” said Robbins Schug. “It is important to incorporate anthropological insights into policy and planning efforts to avoid dangerous popular misconceptions about human nature and human evolution. Social, cultural and historical factors all play a role in shaping human responses to climate and environmental change.”

Professors Kelly Knudson and Christopher Stojanowski with the School of Human Evolution and Social Change were also co-authors of the article.